Plot Summary from IMDB: “A man wanders out of the desert after a four year absence. His brother finds him, and together they return to L.A. to reunite the man with his young son. Soon after, he and the boy set out to locate the mother of the child, who left shortly after the man disappeared.”

—————————————————————–

Following is my entry for The Criterion Blogathon, hosted November 16-21, 2015, by the blogs Criterion Blues, Speakeasy, and Silver Screenings. Head over to one of these blogs to check out tons of great content.

————————————————————————-

Having done so on 19 August, I think I must have been one of the earliest to claim a title for this blogathon. I actually own a hard copy of Paris, Texas, and though I had not seen it in a while, I remembered that first viewing as a powerful and moving experience, so I picked it. Now I feel a bit like Travis, wandering purposefully, but aimlessly through vast, empty spaces, changing direction occasionally but ultimately making no progress. Like Spirit of the Beehive or Picnic at Hanging Rock, the economy of plot and dialog of Paris Texas make it a difficult film to explore in terms of its storytelling, so instead I’ve tried to approach it on literary and philosophical terms.

|

| View Trailer |

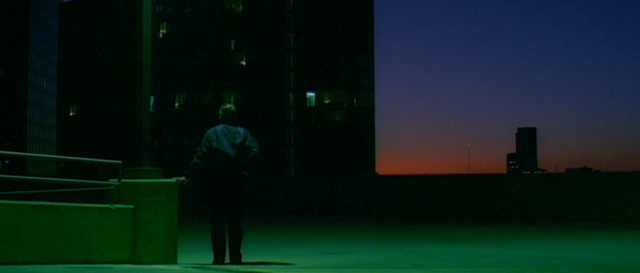

Has there ever been a more arresting depiction of the absurd committed to film than Travis? Walking on the outskirts of Terlingua, Texas, his appearance is bizarre, his face haggard. To use a West Texas expression, he looks rode hard and put up wet, and yet he is wearing a suit and jacket with tie still firmly tied. His actions are likewise puzzling. He takes a drink of the last few drops of water from the plastic milk jug and then carefully screws the top back on only to immediately discard it. We do not know the cause of his suffering or how he has come to be where he is. We know only that he has suffered and yet continues so long as he is physically able relentlessly on toward the void. “What’s out there, Trav?” his brother Walt asks rhetorically, “Nothing. There’s nothing out there.” The American Southwest it may be, but it is also the wasteland. Walt evokes this theme again later in the film with Travis’ son, Hunter. Finding him behind the wheel of the car pretending to be driving, Walt asks him, “Where you going?” “Just driving,” responds Hunter. No doubt it’s better when you can do it at high speed in a 1970 Dodge Challenger, but the metaphysical grounding is the same in this film as it is in Vanishing Point–we are all “just driving.”

As Walt says, there is “nothing out there.” However, this does not mean we must march relentlessly toward nada alone and without solace. We may lose our way occasionally, but so long as we are on this side of the void, there is a chance for redemption. Dr. Ulmer, who examines Travis when he emerges from the desert asks him pointedly: “Do you know what side of the border you are on?” It is the central question of the film. Travis obviously has come perilously close to losing his way irreversibly, but because he has a brother who will go to the considerable effort it takes to intervene, he is still able to be retrieved from the brink. Not all are so fortunate. No one is coming for “the screaming man” whom he encounters on the bridge, and he’s too far gone even if there were. Unlike Travis, who is mute when Walt finds him, the screaming man cannot stop talking; however, if he has a message, it has long since been lost in the cacophony of his own mind. Both have lost the ability to communicate. Walt, Ann, and Hunter are on one side of the border; the screaming man is on the other. Travis, who has himself teetered on the brink, understands this. At first visibly frightened by the screaming man, Travis reaches out to touch him.

Magritte’s Pipe

The ability to communicate is what allows us to form bonds with one another, such as those that exist between brothers or spouses or fathers and sons. When we lose the ability to communicate, we risk becoming lost like the screaming man. Unfortunately for us, the tools we have for communication, such as language, are woefully inadequate and misunderstandings abound. Travis’ first word to Walt is “Paris.” The audience knows from the film’s title that Travis is referring to Paris, Texas, but Walt of course thinks he means Paris, France. The misunderstanding is then extended to include the photograph itself. When Walt asks Travis where he got it, he responds that he bought it. Travis means the land shown in the picture rather than the picture itself, but, again, Walt misunderstands. This Magritte’s pipe type confusion between the thing itself and some representation thereof recurs later as they are watching 16mm films of a family vacation when they were all still together. When Ann identifies Natassia Kinski’s character as Hunter’s mother, Hunter corrects her, saying, “That’s not really her; that’s only her in a movie.” Such small scale confusions and deceptions happen all the time and do not normally set us adrift and lead to perilous journeys into the desert. It’s when they are complicated by our emotions and scaled to fit those things most important to us in our lives that they become dangerous as they did for Travis and Jane. When Travis finds Jane, having since gone through the long dark night of the soul, he finally has the clarity he needs to be able to communicate their story poignantly, even through the artificial barriers of phone and glass. The pathos of the moment reaches us so effectively because of Stanton’s superb performance and because we are intimately familiar with the steep price his character has paid.

Conclusion

What a brilliant, beautiful, melancholy film Paris, Texas is. Brilliant in its execution, beautiful in its performances, and melancholy in its presentation of the plain and simple truth of man’s existential angst and the fact that the road to redemption–our relationships with one another–is also the road to destruction. To say we hurt the ones we love most is trite, but showing the devastating effect of the aftermath as effectively as this film does is anything but. Let’s hope we’re all watching this from a spot comfortably within the safety zone. When communication breaks down, it can get pretty rough out there. Just ask Travis.

I love that line: “That's not really her; that's only her in a movie.” Brilliant.

Your review is great. It is a fitting tribute to “Paris, Texas”. Would you say this film is gaining a little more traction in terms of popularity in the past few years? I see more and more people talking about it.

Thanks for joining the blogathon with your insightful review. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you very much. To tell the truth, I was a little disheartened that I hand't gotten even a single comment, and then I saw that I did in fact have one “awaiting moderation,” so, again, thanks! It's such a brilliant film, I never really thought about it as not being terribly popular, but I certainly think the film warrants it. For some reason, it reminds me more of a short story where every word counts.

LikeLike

This is a well-written tribute to a lovely movie. I'm shocked that you haven't had a bigger response. I'll bet some folks (like me) are making their way through the blogathon list, and it's taking awhile to read everything.

LikeLike

Thanks!!!

LikeLike

This comment has been removed by the author.

LikeLike